Perceptions of China among Southeast Asian youth

Source: GLOBALWEB INDEX

When talking about improving China’s international communication capacity, General Secretary Xi Jinping called for the use of targeted communication strategies that can cater to the demand of different regions, countries and groups of audiences to spread Chinese stories and voices globally, and with an approach that is tailored to particular regions and audiences.

Given the complex international landscape, Southeast Asia will become a key region for China’s neighboring diplomacy and economic cooperation. Data shows that the number of youth aged 15 to 35 in Southeast Asia reached 213 million in 2021. As we enter the intelligent and digital era, youth have gradually become pioneers for social reform and the backbone of social development thanks to their entrepreneurial skills and their ready acceptance of new technology and new thinking. Therefore, whether or not Southeast Asian youth—a community accounting for one third of the regional population—understands and trusts China makes a huge difference to the advancement of the Belt and Road Initiative and a human community with a shared future.

Online habits

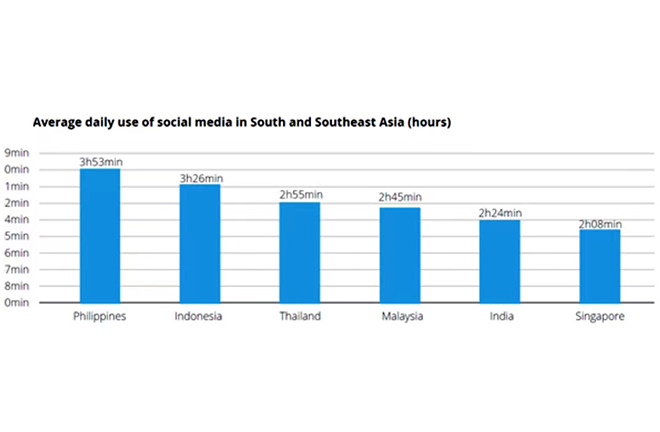

Southeast Asian youth rely on mobile media. According to a study released in 2018, over 90% of Southeast Asians access the internet with smartphones, and their online time using the mobile internet far exceeds other regions. Thai netizens rank first in the world in terms of their average daily time online, which lasts for four hours and 56 minutes. Users in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia spend on average around four hours a day using the mobile internet, and rank among the top ten nations globally. These figures are not only higher than those in China, but also left Europe, the US, and Japan far behind.

As the mobile internet becomes more ubiquitous, small-screen mobile terminals are replacing big-screen televisions and computers as Southeast Asian youth’ preferred source for video consumption. Another study shows that over 50% of people in the region prefer to watch videos on their phones, and the number of users watching videos on smartphones in Thailand and Indonesia far exceed that of computers and televisions.

Their second most predominant online habit is the use of social media. Social media has become an indispensable part in the everyday life among Southeast Asian youth. Malaysia ranks first at 81%, followed by Singapore (79%), the Philippines (67%), and Indonesia (59%).

Youth in the region demonstrate a strong proclivity towards self-expression, and social media platforms provide their primary outlet. Youth are willing to obtain information and exchange ideas on social media. Therefore, social media platforms have become an important instrument for polling, thus play a big part in decision-making and elections. Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter, among other social media, are the first choices of young users in the region. Apart from international platforms, some local platforms like Thailand’s Pantip are also popular among local users.

Perceptions held regarding China among youth from Southeast Asian countries are varied and complex. Most countries in the region have a small to medium scale. Some are alert to and distrustful of their geographical neighbor China, due to the disparity in national strength and conflicts in the South China Sea.

At the same time, Southeast Asian countries share a profound cultural origin with China. With many Chinese people dwelling in their countries throughout history, some of these countries have been deeply influenced by Confucian culture. Their people’s daily habits, way of thinking, and religious beliefs have a great deal in common with Chinese people, making it easier to understand and accept Chinese culture. For example, Chinese costume dramas are well-received by young people in the region.

In recent years, China’s economic growth has inspired many neighboring developing countries, while cross-border economic cooperation has also generated many job opportunities and potential for career development for the youth there. This is widely recognized in the region.

However, research also shows that perceptions of China differ among key countries in the region. Thai people’s perceptions are generally more positive, while Vietnamese impressions run in the opposite direction, and people from other countries hold a relatively neutral attitude towards China. Southeast Asian students studying in China rate China more positively than India, but less highly than the US and Japan. This shows that there is much room for Southeast Asian youth to improve their perceptions of China.

Targeted communication

To promote humanistic exchanges, foster people-to-people exchanges, and tell the Chinese story among Southeast Asian youth growing up in the internet era, we may consider the following approaches.

We need to emphasize mobile media and promote people-to-people exchanges through social media platforms. In Southeast Asia, where mobile media has an absolute advantage, we need to update outdated and traditional external communication methods and tell stories about Chinese using social, intelligent, and scenario-based communication. Mainstream media should consider this group’s unique characteristics, choose topics according to young people’s interests, and deliver China’s voice in an accepted way. They should also follow the communication rules for social media, adopt fragmented and personalized distribution methods for accurate communication, and pay full attention to the community influence of young opinion leaders.

At the same time, mainstream media can try to integrate private resources, such as self-media, and lead interactive exchanges with Southeast Asian youth groups on social media platforms. This kind of rapid communication and interactions between people of different countries and cultures across time and space not only promotes people-to-people exchanges between the two sides, but also help us quickly identify misconceptions among Southeast Asian youth about China’s economic development, foreign policies, and the Belt and Road Initiative, and identify the risks of these international online public opinions.

We should focus on our strengths, and spread Chinese culture in a proper way. Enterprises “going abroad” can help play a role. The U.S. has gained a first-mover advantage in the social media field in Southeast Asia, so we can use “going abroad” enterprises to explore new fields, open up new tracks, and make Chinese voices heard. We should promote public diplomacy and encourage young elites to approach and understand China. The U.S. and Japan have launched several youth diplomacy programs in Southeast Asia, including the “Southeast Asia Youth Leadership Initiative” and the “Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Learning” of the United States, and the “Southeast Asia Youth Boat” and “YMCA Alliance” of Japan. These public diplomacy programs have not only promoted youth exchanges between the different cultures, but have also effectively enhanced the national images of these countries among Southeast Asian youth groups. We can learn from the experiences of the U.S. and Japan to promote public diplomacy between Chinese and Southeast Asian youth, provide experience and assistance to Southeast Asian youth in entrepreneurship and development, invite Southeast Asian youth leaders and scholars to study and exchange knowledge in China, and encourage young elites to welcome closer understandings of China.

Youth are the future of the country and the region. We should target youth groups for accurate communication, especially in Southeast Asia, where youth groups account for one-third of the total population. This will enhance local youth groups’ understanding of China and increase recognition of Chinese culture among young people. This is a feasible way to achieve stable and far-reaching relations between China and Southeast Asia in the form of people-to-people exchanges.

Li Wenfang is a lecturer at the School of Journalism and Communication at Xi’an International Studies University.

Edited by WENG RONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE