Jade working in ancient China

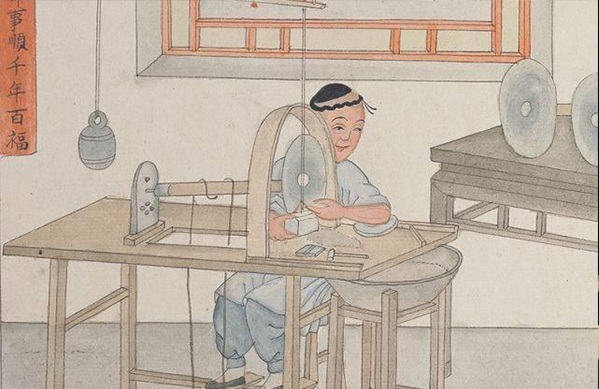

FILE PHOTO: A painting from the Yuzuo Tu album, painted by the Qing Dynasty artist Li Dengyuan in 1891, illustrating an artisan polishing jade with a tuoji

To study ancient Chinese jade ware, it is necessary to understand ancient jade working crafts. The heyday of jade working art is always inseparable from the innovation of tools.

'Jieyu' sand

There are very few records about ancient jade working tools in documents. The Book of Songs [the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry] mentions the method of jade working—carving and polishing with “stones.” The “stones” refer to an indispensable medium for working at jade—jieyu sands.

The early jieyu sand was ordinary sand, which contained many quartz particles with higher hardness than jade, playing a key role in overriding the abrasiveness of jade and subduing it to molding. Chipping and polishing jade with jieyu sand finally separated jade working procedures from stone processing and became a unique fine handicraft industry.

Metal tools

The use of bronze tools is a major change in jade working. Traces of using bronze tools [in jade working] can still be found during the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE). By the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), however, jade working had been dominated by iron tools, and since then, the history of ancient Chinese jade working craftsmanship has been mainly based on iron tools.

The most important carrier of the progress of tools is the development of the tuoji [a grinding machine powered by hand or foot-treadles and grinders; by adding quartz and water between the grinders and jade, artisans can grind and process the mineral].

In the Neolithic period, there might have been primitive tuoji, which were powered by hand and operated jointly by several people. The grinders might have been made of natural materials such as stone, wood, bamboo, bone, or pottery.

The low-table-style bronze tuoji were mainly used from the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE) and Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) dynasties to the late Spring and Autumn Period. At that time, people were in the posture of kneeling and sitting when using the low-table-style tuoji. The tuoji was powered by hand, and the operation became increasingly mature. Later, the application of bronze tools accelerated the speed of jade working.

From the Warring States Period (770–476 BCE) to the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589) was the era of the low-table-style iron tuoji. Since artisans were still in the posture of sitting on the ground, the tuoji remained in a low-table style. Due to the improvement of iron smelting technology, the grinders of tuoji were made from iron. Iron is harder than bronze, which further improved the speed of jade working.

The high-table-style iron tuoji was used from the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties to the early 1960s. At that time, the tuoji was developed into a high-table style, operated by one person and powered by foot-treadles. It was also known as shuideng during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. Since the tuoji was powered by feet, which provided more power, the speed of jade working was faster.

The era of modern jade working is from the 1960s to the present. During this period, the material for the frame of the tuoji changed from wood to iron, and the grinder was made from steel. Electricity replaced the foot-treadles, and the speed of jade working is far faster.

Jade is a hard stone and working it [with primitive tools] would have required a great deal of time and effort, [which, of course, only added to its value]. “The jade uncut will not form a vessel for use; and if men do not learn, they do not know the way in which they should go” (trans. James Legge). Just as the saying goes, jade working and personal cultivation cannot be achieved overnight.

Xu Lin is a research librarian from the Department of Objects and Decorative Arts at the Palace Museum.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE