Living in a multipolar world

To illustrate my point, let me briefly rehearse the history of globalization as the history of the diminishing importance of territoriality, beginning with the fall of the Roman empire around 500 CE. At that point an ambition for global outreach and dominance began to develop in Europe. Prior to this geopolitical situation, the ambition around the world was first and foremost an extensive regional yet not a global dominance. China built its wall, and the Roman empire only expanded within what was then called limits, limes.

History of globalization

A compressed and simplified version of the history of globalization may therefore be described as a succession of four global flows of a growing complexity in which earlier dominant flows are inscribed and modified in those that follow – flows being taken in the sense of Appadurai as the global circulation of objects, ideas and forces in networks with shifting and often multiple centers.

First, from about 800 to 1500 CE we meet ideological flows of ideas and belief systems of which the Roman Catholic church is the first to formulate an ambition of actively spreading its doctrine across the entire globe, “to all peoples” is the term in the Bible. Christianity was immediately followed by Islam, both religions being institutionalized by and affiliated with state powers for the next hundreds of years when crusades and jihads produced vast and competing expansions.

Second, from about 1500 to 1900 came the geographical flows of objects, people, materials and resources as an effect of the global European colonization, while earlier colonizations in Asia, Africa and Latin America were regional in nature. This phase of globalization is first of all of a territorial nature, but colonization also included the ideological flows transporting Christianity and to a lesser extent Islam around the world.

Third, from around 1800 to post-World War II the industrial flows developed, defined by an endeavour to gain global access to resources and markets and spurred by technological innovations. This phase coincides with the late development of geographical colonization and the rise of capitalism and its flows of money and financial instruments. Moreover, this phase of globalization also transformed the ideological flows of religions into flows of political ideologies, most notably liberalism and communism. Finally, this phase relocated the centers of the geographical flows, making the Middle East with oil resources one, yet not the only new center, a process which is very much embedded in today’s globalization. While the two first waves of globalization to a large extent are dominated by Europe, during this third phase other parts of the world became active drivers: US, Japan and the Soviet Union.

Fourth, from about 1945 until today the communicative flows of networks marked a new phase of globalization – within a broad definition of communication ranging from transmission of information to travel and trade. These flows are defined by four features: (1) new technologies, digital technologies in particular, which are decisive for the reshaping of industrial processes with global supply chains; (2) the digitized logistics of trade routes; (3) the digitized financial processes; and finally, (4) the global media circulation of information, ideas and research based innovation. The remarkable effect of this most recent phase of globalization is that geography and territorial control have become less important than cross-boundary networks in terms of production, trade, innovation, finance and cultural encounters. It is during this phase that China has become a key player in the multipolar globalized world of many parallel flows.

Coming back to the title of the conference―China and the World, it is clear that the latest development of globalization redefines both China and the world, the world now being a compound of interacting flows and networks with moving centers of which China has become one of the centers for some of the flows, in particular industrial and technological flows. In this historical juncture, less importance is attributed to territory in order for a country, big or small, to actively enter and direct the flows, and more importance is determined by its capacity for innovation on multiple levels. The huge move forward for a small country like my own, Denmark, with less than 6 million people as well as for a big country like China after 1979 is to a large extent based on their growing capacity to forge and contribute to the nature of these flows–in production, trade, finance, politics, technology, infrastructure, education and research within an increasingly diversified national economy that reflects their participation in the recent developments of globalization. Such countries have learned to live in, benefit from and influence a multipolar world of flows.

The diversity of the homeland

China’s active engagement in the diversity of the multipolar world of industrial, financial, technological and communicative flows also impacts the domestic diversity and changes within the boundaries of China, today with a growing public awareness of that impact. Even the local fruit vendors, and not only younger ones, receive their payment via a QR code on the mobile phone with a WeChat app. Tencent QQ, Weibo and other platforms function like similar platforms anywhere in the world, while Tiktok is used across the world.

Classical China, even in periods with a strong centralized governmental structure, was also highly diverse in terms of local languages, minorities, habits, climate zones and a good deal more. Yet, back then few people were able to witness the actual diversity of China. Today, due to the impressive domestic infrastructure of cables, roads and rails, diversity is no longer “out there” in different localities, but can be experienced by all Chinese citizens with their own eyes, both the diversity of classical Chinese sites and customs and not least the rapid changes that have taken place more recently. Students now relocate themselves across the country for their education and later for work, while young families establish themselves beyond the local confinements of their parents, and in growing numbers they are able to travel the world as students, researchers, employees, migrants or tourists. In other words, China’s engagement in all the flows of the multipolar world is not only reflected in domestic diversity and changes, but also in a growing awareness among people of this entanglement of China and the world.

The bridge to the future

I have used the metaphor of the bridge in some of my last paragraphs. The bridge is an old Chinese image of transition across a gap, personally and socially. Thinking of the transitions pertaining to modern China in the globalized world, I see for my eyes two marvelous bridges. One is the impressive Sutong Yangtze River Bridge from 2008 near Suzhou in Jiangsu Province; the other is the beautiful ancient Hongqiao Bridge in Fenghuang in Hunan Province which since the Ming dynasty has crossed the Tuo River.

For me, the first bridge symbolizes China’s transition into the globalized world of industrial, financial, technological and communicative flows. The second symbolizes the transition from the quiet diversity of traditional China to the restless diversity of modern China. The Hongqiao Bridge is the continuation of a long tradition for high-level technological skills, and, by giving name to one of the international airports in Shanghai (and to many other sites as well), this bridge both unites the old with the new and connects China with the world.

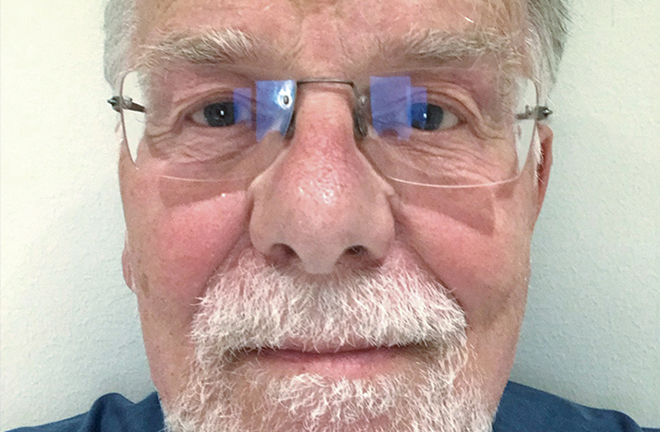

Svend Erik Larsen is former vice president of the Academia Europaea and professor emeritus from Aarhus University, Denmark. This article was edited from his video speech submitted to the forum.

Edited by BAI LE

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE