National traits vital in modernizing calligraphic aesthetics

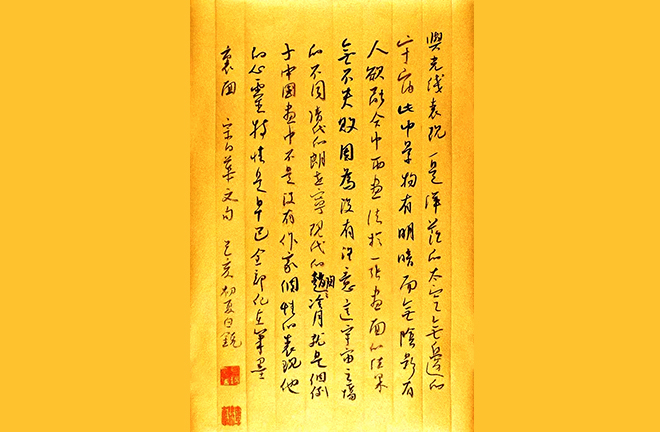

FILE PHOTO: A calligraphy work of renowned Chinese aesthetician and philosopher Zong Baihua (1897–1986)

At the opening ceremony of the 11th National Congress of China Federation of Literary and Art Circles and the 10th National Congress of China Writers Association held in December 2021, General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee Xi Jinping said in his speech that national characteristics of literature and art represent the cultural hallmarks of a nation. Among numerous genres of literature and art, shufa, calligraphy of the Chinese writing system, is undoubtedly very typical of the nation. Focusing on the national art of shufa, Chinese calligraphic aesthetics epitomizes academic discourse of traditional Chinese research paradigms.

As exchanges in thought culture and scholarly communication intensify between China and the West, examining the aesthetic mechanism of shufa through a cross-cultural lens can reveal traces of modernization in theoretical construction of Chinese calligraphic aesthetics and criticism, while showcasing national traditional art traits.

National characteristics

Chinese calligraphic aesthetics is nationally distinctive in that its research object, shufa, is unique. Renowned Chinese aesthetician and philosopher Zong Baihua noted that shufa is a national art that can express the loftiest artistic yijing (idea-scapes or mood) and sentiments. Changes in calligraphic styles can even contribute to the periodization of Chinese art history. In short, shufa can best represent the Chinese aesthetic and artistic spirit.

As an expressive art, calligraphy is not committed to conveying meaning through symbols, but to expressing calligraphers’ emotions through its aesthetic form or grammar. From the perspective of a medium, brushes and ink can be elevated as part of calligraphic aesthetics because they are not merely tools for writing, but due also to aesthetic levels determined by their role as artistic mediums.

While being fully displayed in Chinese calligraphic aesthetics, the national characteristics of brushes and ink are likewise valued in painting theory, which involves another crucial feature of traditional calligraphic aesthetics: mutual reference between calligraphy and other forms of art.

Chinese painting theory emphasizes the mutual reference between calligraphy and painting. In the aesthetic mechanism of traditional painting, calligraphy is often used as reference. For example, Zong pointed out that the spatial configuration in traditional Chinese painting is a spatial creation of calligraphy. Space in shufa is not simply about arranging and displacing Chinese characters. It also contains the rhythm of time. Therefore, Chinese calligraphy carries attributes that mirror music and dance. Shufa’s spatial characteristics concretely reflect the temporalization of space in Chinese art.

The relationship between calligraphy and literature is even more complicated. Calligraphy is mostly applied to famous works of poetry and prose, and as such, literary requirements are layered on top of calligraphy theory. A complementarity between calligraphy and criticism is an ideal of shufa study, proposed and practiced by calligrapher and calligraphic theorist Zhang Huaiguan from the Tang Dynasty (618–907).

Another key trait of traditional calligraphic aesthetics is that it has profound implications for life. The tradition of harmony between humans and heaven in Chinese philosophy emphasizes the synchronization and symbiosis between man and nature—to internalize nature among humans. Calligraphic aesthetics considers shufa a living expression of vigor among all beings in nature.

In terms of creation theory, Chinese calligraphic aesthetics underscores harmony between calligraphy and nature. However, the concept of shufa ziran, literally “nature of calligraphy,” in creation theory, is different from the Western “imitation” theory. The nature of calligraphy is about creating calligraphic imageries inspired by natural phenomena, rather than imitating, reflecting, or expressing nature. It has the spirit of nature.

Moreover, traditional calligraphic aesthetics leverages a great many objects and phenomena in nature, which is summarized by famed French-Chinese artist and philosopher Ping-Ming Hsiung as yuwu (object analogy), using natural objects or phenomena to analogize or describe the beauty of calligraphy. This, together with literary and painting theories, contributes to the characteristics of experiential perception and poetic expression in Chinese classical aesthetics, which is widely different from the Western speculative paradigm of theoretical construction.

Calligraphic aesthetics, an aesthetic exploration of a particular art form, is universally significant for traditional Chinese aesthetics. Zong suggested 60 years ago that we could glimpse the categories of Chinese aesthetics from the structural beauty of shufa, as discussed by ancient Chinese. For example, the category of shi (force or dynamic configuration) in Chinese aesthetics originated from the same concept in Chinese military tactics, and then transitioned to shufa, so the shi of Chinese aesthetics stemmed from shufa. Thus, it is feasible to build a theoretical system of Chinese aesthetics from calligraphic aesthetics.

Modernization attempts

Compared with literary theory, painting theory, and philosophical aesthetics, Chinese calligraphic aesthetics is, in reality, less impacted by Western theory and thought trends, and by the discipline of modern research paradigms. It has retained its traditional and national character.

When exploring the issue of calligraphy’s artistic ontology and aesthetic mechanism, Chinese calligraphic aesthetics should end stereotypical image-, experience-, and perception-based criticism of traditional calligraphic study. This is essential on its path to modernization.

At the end of his book Theoretical System of Chinese Calligraphy, Hsiung called for breakthroughs in the system, concepts, and methodology of traditional Chinese calligraphic theory under the impact of Western culture. The questions he raised are significant topics for the modernization of the field, such as: How should scholars organize previous theories with new tools and thus build a new system? How can artists access new possibilities, seek new paths, create new inky images, and open up new frontiers in calligraphic aesthetics?

The modernization of calligraphic aesthetics manifests in reforms to approaches. Since modern times, calligraphic aesthetics has clearly divorced itself from the critical model which emphasizes experience, perception, and rhetoric, integrating modern academic paradigms such as logical speculation, generalization, and analysis, into the understanding of calligraphy as a national art form. Representatives of this reform include Liang Qichao, Zhang Yinlin, Lin Yutang, and Zong Baihua.

Roughly after the reform and opening up, many calligraphic aestheticians were obsessed with Western methodologies, losing themselves to it. During the methodology craze, in a wide range of disciplines, some “one-size-fits-all” methodologies were unavoidably employed in Chinese calligraphic aesthetics. Nonetheless, some other scholars dug deeper into Chinese calligraphy using visual perception, analysis of forms, and semiotic approaches, and major breakthroughs were achieved.

Hsiung proposed drawing upon and absorbing foreign concepts and methods from both rationality and anti-rationality, on the pretext that the abstractness of Chinese calligraphy is like Western abstract art. To be more specific, summarizing a set of rules on shufa with the help of modern Western visual psychology (such as Gestalt Psychology and modern experimental psychology), surrealism, and abstractionism will not only illuminate nationalized calligraphic study, but also bring in new philosophies for calligraphy education in China.

Correlatively, although contemporary calligrapher Qiu Zhenzhong acknowledged calligraphy’s nature of abstract composition, he was soberly aware that the component analysis method for all visual arts was unable to move deep into the structure of Chinese calligraphic forms, so he called for a new analytical tool for the component analysis of shufa. This proved that when boldly using Western methods of artistic criticism, it is vital to take into full consideration the unique nature of shufa, whether considering its basic unit—Chinese characters— or peculiarity in time and space.

Visual psychology and abstract semiotic analysis are more inclined to regard calligraphy as an art of composition, yet its generative nature is often overlooked. It is presented as text with expressive and aesthetic functions, based on Chinese characters, the physical form of the Chinese language. Hence the revelation of calligraphy’s graphical nature can never lead to the core of traditional calligraphic aesthetics. In this light, it is necessary to go back to the plain logic that calligraphy is about written language symbols, Chinese characters in the case of China. By comparison, some self-purported innovative modern calligraphy is actually imitating Western abstract art.

How can writing be aesthetically pleasing while remaining legible? This has remained an unsolved essential question to calligraphic aesthetics, and the point of departure from which the field can achieve most modern theoretical innovation based on phenomenology.

Regarding this issue, literary aesthetician Zhao Xianzhang put forward the concept of shuxiang (calligraphic image). In his opinion, calligraphic images illustrate texts and emanate the essence of calligraphy, thus striking a chord between textual and calligraphic implications.

Zhao considered shufa the best of Chinese fine arts, because it is an aesthetic representation of language, which he termed “the homeland of existence,” whereas painting is just a “thin film of existence.” He was mainly devoted to articulating the transformation from literary art into calligraphy, maintaining that translation from language arts to graphic arts concerns the fundamental question of how calligraphy becomes artistic.

On this basis, Zhao held that essentially, invisible literary language images are transformed into visible calligraphic images via images of Chinese characters. Zhao’s literary calligraphy image theory is, on the one hand, a creative exploration of the generative mechanism of calligraphy’s ontology. On the other hand, it is a meaningful reflection on the modernization of Chinese calligraphic aesthetics, exemplifying a paradigm shift in the field.

Both Hsiung’s research on theoretical resources from Western visual psychology and modern abstractionism, based on the abstract styling features of shufa, and Zhao’s quest for in-depth phenomenological interpretations of calligraphy as the ontology of graphic arts, are great endeavors in the modernization of calligraphic aesthetics.

Nationalization and modernization are the two dimensions of research in calligraphic aesthetics. National traits are not only the breakthrough point in the field’s modernization, but also its logical starting point, and the last stand.

When seeking more effective research methodologies for shufa, a Chinese national art, we should ground ourselves exactly in its national characteristics as well as those of calligraphic aesthetics. The experiential nature, literary attributes, and implications for life, of traditional calligraphic aesthetics, are reflexive to modern calligraphic aesthetics. Studying calligraphy’s ontology and visual reception mechanism from new perspectives and with new approaches, particularly Western philosophical, aesthetic, and art research methods, is conducive to advancing the modernization of calligraphic aesthetics. Nationalization and modernization jointly point to the future of Chinese calligraphic aesthetics.

Han Qingyu is a professor of aesthetics at Shandong University.

Edited by CHEN MIRONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE