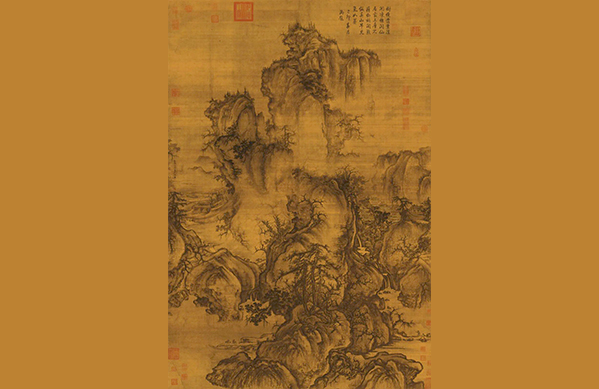

FILE PHOTO: “Early Spring” by the Northern Song artist Guo Xi (c. 1020–1090)

In his work Linquan Gaozhi (Lofty Record of Forests and Streams), Guo Xi [one of the most famous artists of the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127)] mentioned that there are thoes who regarded painting as “poetry with shape” and poetry as “shapeless painting.” Since then, this idea has become an important theoretical topic depicting the relationship between poetry and painting in the early Northern Song Dynasty. However, this depiction underwent changes in the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty, during which the opinion that regarded painting as “poetry with shape” was replaced by the one that regarded painting as “voiceless poetry,” and the concept of “voiceless poetry” formalized in the late Northern Song Dynasty. (There is a precondition for this discussion: just as the renowned literary scholar Ch’ien Chung-shu put forward in his article “Chinese Poetry and Chinese Painting,” the discussions of “poetry with shape” and “voiceless poetry” by the Song Dynasty people, as well as the related theories adopted by later generations, specifically referred to landscape poems and paintings, with a small portion depicting flowers and birds.) The transformation of painting from “poetry with shape” to “voiceless poetry” embodied amazing literary and artistic ideas.

Poetic transformation of painting

Painting is an art form composed of lines and colors. The title of “poetry with shape” is derived from the observation of the relationship between poetry and painting based on the nature of painting. The transformation from “poetry with shape” to “voiceless poetry” meant that the “voice” of poetry replaced the “shape” of painting, which indicated that the aesthetic standard of poetry had been applied in the field of painting. It also revealed the process of literati implanting thinking modes of poetry into the theories of painting.

The Song Dynasty (960–1279) people gradually paid attention to the artists’ self-cultivation, and regarded it as a standard for painting. Artists’ self-cultivation proposed by the Song people included three aspects: literary attainments, life experiences, and research and inheritance of artistic traditions. In the Song era, many literati engaged in painting. Therefore, paintings with inscribed poems on them as well as poetic paintings were created in large numbers. Some paintings were created according to poems that were composed previously, while some poems were inspired by paintings. Renowned Song scholar Su Shi (1037–1101) inscribed a painting titled “Misty River, Layered Peaks” [now preserved in the Shanghai Museum] by the Song artist Wang Shen (c. 1048–1104) with an accompanying poem. Later, Wang Shen wrote a poem with reference to Su’s poem. Then, Su wrote another poem in response to Wang, which was answered by yet another new poem by Wang. This interaction corresponded with what Su wrote [when he inscribed a painting by Wang Wei (699–759), renowned poet of the Tang Dynasty (618–906)]—“When one savors Wang Wei’s poems, there are paintings in them./ When one looks at Wang Wei’s paintings, there are poems.” The poetic transformation of painting in the Northern Song Dynasty became a characteristic and fine tradition of Chinese painting.

Aesthetic expression

The transition from “poetry with shape” to “voiceless poetry” was also related to the birth of literati paintings in the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty, and the aesthetic spirit of shangyi [an idea emphasizing spontaneity and expressiveness] in the Song era. Su Shi was considered the pioneer of literati paintings [a form of Chinese painting created by scholar-artists who focused more on personal expression than formal representation]. Su said, “Appreciating literati paintings is like looking at galloping steeds of the world: one must choose only those that work well in both structure and vision. A mediocre painter pays too much attention to trifles such as the hide and mane, horse whip, manger, and fodder, which are not quite able to enhance our aspirations. We would start to feel tired after we have looked at the first ten inches or so of such a painting.” Su believed that paintings produced by literati should be distinguished from those by skilled artisans, as the former focused on revealing painters’ aesthetic cultivation and personal feelings, while the latter focused on demonstrating craftsmanship. Su believed that “those who discuss painting in terms of life-likeness have the understanding equal to that of a child.” In Su’s opinion, literati and skilled artisans were different in education and self-cultivation. Literati should pursue more than a direct copy of the real world, because artisans could draw the outer appearance of a subject with more skill. Therefore, literati painting should focus on a human’s innate attachment to nature, reaching a state where the scene described presents poetic imagery, and allows viewers to wander in their imaginations. This was Su’s aesthetic proposition. He also expressed similar views in his evaluation of calligraphy and poetry—“I once talked about calligraphy, and I said that the calligraphic works of Zhong Yao [a famous Chinese calligrapher, 151–230] and Wang Xizhi [revered today as the Sage of Calligraphy, 303–361] were natural, leisurely, simple, yet profound, and their artistic appeal went far beyond the calligraphic works themselves.” As for poetry, Su said, “Although there are other poets after Li Bai and Du Fu [both are considered among the greatest of ancient Chinese poets], they were hardly able to reach a height required to express the content of their poems. Few had the ingenious quality of their poetic predecessors. Only Wei Yingwu (737–792) and Liu Zongyuan (773–819) far exceeded others, because in their poetry, rich delicacy dwells in vintage simplicity and nuanced profundity in serene composure.”

During the middle and late Northern Song Dynasty, literati gradually abandoned the concept of “poetry with shape” and switched to “voiceless poetry.” This shift was deeply rooted in an intellectual and cultural context. “Voiceless poetry” not only emphasized the absence of sound from painting, but also highlighted the “absence” itself. Sound, taste, and color were listed as the three major aesthetic categories in ancient China. However, during the Northern Song Dynasty, influenced by the aesthetic pursuit of Zen philosophy, people considered a good artwork to not only be “voiceless” but also “tasteless” [a poetic concept that the utmost taste should transcend any worldly criterion] and “colorless” [in Buddhist terminology, se (color) or rūpa, refers to perceivable things; the term colorless reflects the spiritual magnanimity and the open, pluralistic worldview of ancient Chinese scholarship]. Under the influence of this aesthetic view, ink wash paintings emerged in large numbers, featuring ingenious use of empty space.

This transformation was inseparable from the special cultural context of the Northern Song Dynasty, when Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism had a profound influence on literati. The Confucian classic I Ching advocates returning to simplicity after going through splendor and glamor. Inspired by this thought, Su went on to put forth the notion that “what seems most plain in the world is in fact the most resplendent” [A notion that echoes the author’s mild and placid temperament, showing his mental attitude and spiritual realm after he had gone through life’s hardships and struggles]. According to the Taoist classic Zhuangzi, “the empty apartment is filled with light through it. Felicitous influences rest (in the mind thus emblemed), as in their proper resting place. Even when they do not so rest, we have what is called (the body) seated and (the mind) galloping abroad. The information that comes through the ears and eyes is comprehended internally, and the knowledge of the mind becomes something external: (when this is the case), the spiritual intelligences will come” (trans. James Legge). Therefore, [literati] painters advocated that the empty space was where the subtlety of the painting rested. The Buddhist concepts of se (rūpa) and kong [a Buddhist concept of emptiness, which denotes that things do not have a constant or unchanging essence] also had a profound impact on the aesthetic consciousness of the Northern Song literati. Influenced by the Buddhist idea of “se ji shi kong,” or “form is empty by itself,” the Song Dynasty scholars preferred to discover the infinite vitality of life from “emptiness.”

The change of painting style in the Northern Song Dynasty reflected a poetic orientation nourished by the aesthetic atmosphere of the times. This poetic orientation was brought about by Northern Song painters and poets’ deeper understanding of the aesthetic characteristics of painting and poetry. Their unique taste and cosmic space-time awareness played an important role in this transformation. The Northern Song Dynasty saw further progresses in painting and theoretical exploration, including the challenge to traditional colored painting set by landscape painting, figure painting being gradually replaced by ink wash painting, and reconsideration of the relationship between poetry and painting. These processes had a profound impact on the history of Chinese painting and aesthetics.

Kang Qian is from the Department of Chinese Language and Literature at Peking University.

Edited by REN GUANHONG

PRINT

PRINT CLOSE

CLOSE